COMING BACK FROM THE BRINK

©TOM BIBLE2017

3,400 WORDS

BY TOM BIBLE

16 PHOTOS

OVERVIEW

This is a story about 5 remarkable cancer survivors - all of whom had been diagnosed with very advanced cancer - so advanced that their doctors had given them months to live. Full of despair, these cancer patients went home to die.

However in the next few days something deep within them clicked - telling them not to give up but to fight for their lives.

And so they began to look around - tracking down other cancer survivors, looking for doctors willing to support them with complementary therapies, changing their diets and exercising again, undergoing counselling, learning new mind/ body techniques such as visualisation - most importantly though, learning to listen to their own intuition

COMING BACK FROM THE BRINK

To anyone with an ordinary attitude to health and exercise – who drinks more than they ought to, or has a gym membership but doesn’t always go – watching 71-year-old Bob Gilley hit the ball around a racquetball court is a shaming experience.

Carrying a knee injury he picked up decades ago, Bob doesn’t move around the court as quickly as he might. That’s not surprising: he’s been semi-retired for 10 years. But Bob is a tough competitor – and when he hits the ball, it’s with the power of a man half his age.

Just how much of a fighter he is becomes clear off court, when Bob recounts his battle with cancer: how he abandoned chemotherapy, followed a controversial alternative “mind-body” treatment – and survived.

It was 33 years ago when Bob, who owned a successful insurance business in Charlotte, North Carolina, went for a checkup and was told he had a lump in his groin.

After a routine biopsy turned into partial resection of the tumour, specialists diagnosed a “secondary undifferentiated carcinoma”, which had spread to a lymph node. Bob was given less then a 1% chance of survival.

Shattered by the news, Bob underwent some of the strongest chemotherapy available at the time.

But the drugs that targeted his cancer wreaked havoc on his immune system. Each month, he would have bouts of diarrhoea, loss of muscle control, and a constant feeling of being sick. At times, he couldn’t extend his arm. Then, after only a few days of feeling better, it would be time to take the treatment again.

It was after three out of six cycles of chemo that Bob took a decision that terrified his family, and that doctors said might well kill him. He decided to quit, and to pursue an alternative therapy instead.

Nauseous and weak from chemotherapy, he flew to California to meet Dr Carl Simonton, a radiation oncologist and pioneer in mind-body medicine, whom Bob had read about in a magazine.

What Bob found there, he says, was “hope”. “He taught me to relax,” Bob explains. “He showed me how the immune system works: how you could put a foreign object in the bloodstream and how the white cells would be alerted, and how they would attack the invader. I was fascinated.”

As well as offering counselling and nutrition advice, Dr Simonton encouraged Bob to use visualisation techniques – to try to trigger that immune response with his mind.

Relaxed and convinced, Bob went back to see his personal physician in Charlotte, saying he wanted to start the Simonton therapy. To start with, his doctor was worried about the risk of abandoning chemo. But in exchange for support for his decision, Bob offered to come in for regular checks – agreeing that, if his cancer relapsed, he would go back on chemo. The doctor agreed.

“Twice a day,” he says, “I set aside 20 minutes to focus on relaxation and visualisation. I was visualising the cancer as a powerful invader, like a snake or a spider or a creature from outer space or something – and I was seeing my own body attacking it, and winning the battle.”

Bob kept to his side of the bargain. For the first six weeks of the checks, there was no change in his condition: but then one day, says Bob, his doctor said he could no longer feel a lump.

Bob was referred to a radiologist, who confirmed the best possible news: that Bob was clear of cancer.

At first his doctor did not believe him – and left on his lunch hour to go and look at the scans. But the radiologist was right: there was, Bob says, “no evidence of disease”.

It was an extraordinary turnaround. From being given a negligible chance of survival, Bob had followed a therapy unsupported by medical science – and somehow wrested control of his health and his life.

Six weeks later, Bob Gilley was back on the racquetball court. Three months later, he was playing at full speed. Thirty-three years later, he remains cancer-free.

Bob Gilley’s is a true story, and a happy story – but taken on its own, it is not the whole story.

Since Richard Nixon declared war on cancer in 1971, around $50bn has been spent on research into the disease in the US – and still more spent on cancer drugs. Yet in 2005, it is estimated that 570,000 Americans will die from the disease.

These days in the US, just under two-thirds of patients survive cancer after five years; up from around a half 35 years ago. But look at the figures more closely, as an article in Fortune magazine did last year, and you discover that in cancer that has metastasised – spread to another part of the body, as doctors think

Bob Gilley’s did – your chances of surviving have scarcely improved in all that time. An editorial concluded that we spend too much money on drugs to shrink tumours, and not enough on researching the process of metastasis that often leads to death.

Add to that the well-known side-effects of chemotherapy – the hair loss, the nausea, all the symptoms described by Bob Gilley 33 years ago – and it is perhaps no surprise that patients seek alternatives.

By 2000, according to a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association, some $34bn was spent on alternative medicine in the US alone.

Cancer is a significant part of that market. Type the C-word into any internet search engine and you will find links to, and advertisements for, hundreds of supplements or therapies. Many don’t work. Most lack evidence to support their claims. Some may even be unsafe.

A few therapies, though, have shown enough benefit that doctors now recommend them as part of what they call “integrative” medicine; in other words, they are therapies to pursue alongside conventional care.

Dr David Rosenthal is medical director of the Zakim Center for Integrative Therapies, in Boston. He says that cancer patients’ quality of life can be “greatly enhanced” by therapies such as mind-body and exercise programmes, acupuncture, massage and Reiki (therapeutic touch) – because they seem to have a calming effect, often allowing patients to tolerate conventional care.

But that’s still a long way from believing that a patient should refuse chemo if a doctor recommends it.

Dr Rosenthal, also director of health services at Harvard University, is from the progressive wing of the medical establishment. If a patient wants to refuse chemotherapy, he will understand that; but on the basis of the evidence of benefit, he’ll try to persuade them they are making a mistake.

“[Some] people look at chemo as a poison that’s affecting the body; these are people who are feel that they have a control over their cancer and can take care of it themselves. It’s just human nature,” he says.

If a patient stops a course of chemotherapy, then follows another therapy and then pulls through, Dr Rosenthal says, the patient will often credit the alternative therapy for the improvement – when, he says, it was the conventional care that helped (that may or may not be true).

But doctors must shoulder some of the blame, says Dr Rosenthal, if patients believe conventional medicine has nothing to offer them any more. “Some patients are turned off by that first consultation with an oncologist. He says: ‘Well, we’re gonna give you a 10% chance [of survival].’”

But patients don’t want a 10% chance, says Dr Rosenthal: they want a 100% chance. And they may well decide that if a doctor seems too pessimistic, then they don’t want to be under their care.

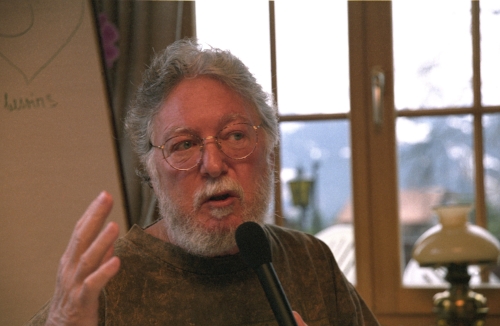

Dr Bernie Siegel, a former Yale University surgeon and something of a legend in the world of mind-body medicine, says doctors should see themselves as coaches, trying to bring out the best in every patient, rather than putting emphasis on what may go wrong.

“I give patients my sermon – do you want to be a survivor?” he says. “Statistics don’t apply to individuals.”

Patients who survive cancer, he suggests, may benefit not, or not only, from the therapy they adopt – but also from their mental approach. And in that, Bob Gilley might not be alone.

Christina Pirello, a TV chef from Philadelphia, understands what it’s like to be looking down the wrong end of a cancer statistic. When she was diagnosed with advanced (Grade IV) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in 1983, aged 26, she was told she had between six and nine months to live - even if she opted for chemotherapy. Her best chance, doctors said, was a bone marrow transplant, which she had a 40% chance of surviving - with only a 50-50 chance of surviving over 5 years after that.

Having seen her mother die painfully of colon cancer after radiation therapy and chemotherapy, Christina refused the therapies - which these days offer a much improved chance of survival in AML - and decided to travel to Italy, where her family lived, to see out her final months in peace.

But something changed when a friend introduced her to Robert Pirello, her husband-to-be, who gave her a book suggesting that cancer could be fought through a strict macrobiotic diet. Under the supervision of a doctor, Christina decided to give the diet a go, and committed herself to it completely.

Christina says she fought her leukemia “the hard way”, and wouldn’t recommend the path she took to everybody - but within two months, she says, her cancer was in remission, and within 18 months it had disappeared. These days, still free of cancer, Christina says her “passion” for healthy eating is what drives her forward in life.

Or take Edgar Bartolucci, who felt left in “no man’s land” after he was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1994. Despite being warned there was a “reasonable chance of complete remission” with chemo, he refused; he had, after all, seen his mother die from cancer after taking chemotherapy. So after a few trips to the local library, he found a doctor who offered a combination of unproven alternative therapies – from high doses of vitamins to shark’s cartilage – plus acupuncture, which is offered as part of integrative care. Edgar has been cancer-free for 11 years; and although there is little independent evidence to support the treatment, Edgar had faith in it from the start.

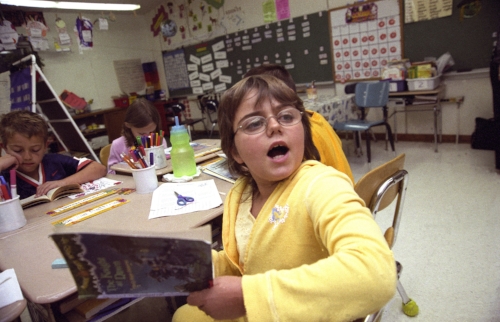

And what about ten-month-old Sophia Gettino, diagnosed with a pineoblastoma, a fast growing tumour, in 1997. Her parents, Jenny and Joe from Syracuse in upstate New York, were told that without chemotherapy, Sophia would die within four to six weeks; with it, she would in any case die within the year.

Despite a warning from a nurse at the hospital, Jenny turned instead to Dr Stanislaw Burzynski, a doctor prescribing an alternative therapy known as antineoplastons, derived from peptides in urine – and which, he says, act as “biochemical micro-switches”, “turning off” genes that cause cancerous cells to grow.

Dr Burzynski was that year to became a controversial figure: he was charged with mail fraud for moving his drugs across state boundaries, a charge he escaped after the jury failed to reach a verdict.

Baby Sophia received 20 hours of intravenous antineoplastons every day for five years, all administered from home.

“We would have to prepare the IV bags every day,” says Jenny. “We would have to get all the air out of them, programme the pump, hook it up safely and carefully to her catheter – that was always something you had to keep sterile and clean. It was quite a commitment.”

Sophia showed signs of improvement after a couple of weeks. Although a scan after eight weeks showed the tumour had grown, subsequent scans showed remission. As she recovered, she was able to wheel around the drug on a small cart, and later still carry it on a special backpack. The treatment continued until she was seven years old, when the second of two PET scans – which can detect whether a tumour is metabolically active (growing) – showed she had beaten the disease.

“In spite of everything that was going on,” says Jenny, “we were still able to be positive; she was happy and healthy and kept right on going, she never complained once.”

Today, Sophia still needs therapy to help her with physical movement, including writing. But she is a happy, sensitive and cancer-free nine-year-old who is doing well in school.

All four tales of survival so far are remarkable in themselves. But of course, you’d look hard to find a doctor prepared to change their practice as a result of any of them.

“Sometimes people don’t realise that the plural of ‘anecdote’ is not ‘evidence’,” says Dr Rosenthal. Like most doctors, he wouldn’t dream of prescribing a drug unless a clinical trial had demonstrated its safety and efficacy, unless it was as part of the trial itself. Evidence, after all, is the founding stone of western medicine.

Alternative therapies such as vitamin supplements, herbs and dietary regimes have generally not been studied in the same way. The fault appears to lie on both sides: the pharmaceutical industry for mainly sponsoring trials of patentable drugs that can show profit, and alternative therapists for failing to keep adequate records of their work.

Yet, understandably, patients don’t see themselves as anecdotes; still less as statistics that go to build up a body of evidence And there is little evidence anyway to explain cases of recovery where conventional therapy wasn’t used: beyond, that is, the term “spontaneous remission”.

That’s something with which Dr Siegel, in particular, takes issue. He prefers a term coined by the Russian writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn, in his book Cancer Ward: “self-induced healing”.

“My feeling,” he says, “was always that if physicians had used that term instead of spontaneous remission, we’d look at it differently.” Spontaneous remission, he says, means “we don’t know what happened - you had a miracle”.

Self-induced healing is an attractive idea, and a nebulous one. But even if it is unproven that patients believe so strongly in their own recovery that they overcome cancer, there can be little doubt that, for Bob Gilley and others, hope was a helpful part of the road to health.

Hope was one thing Susan Silberstein didn’t have much of in 1976. She was a young mother when her husband was diagnosed with a rare spinal tumour – and told that no available treatment could save his life.

Susan turned to medical libraries and also researched alternative therapies. She started calling clinics around the world, but, with her husband in hospital all the time, they weren’t able to try any of them.

“When he died on schedule a year later, he left me with a broken heart and two babies, but I had a burning desire to make a difference.”

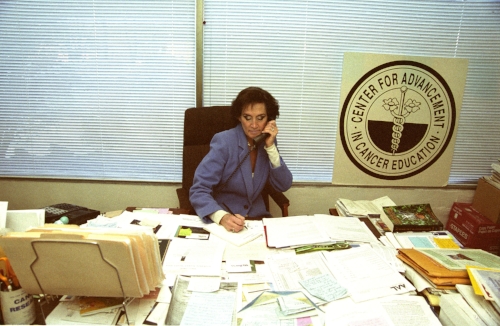

Susan set up the Center for Advancement in Cancer Education (www.beatcancer. org), a counselling service which aims to tell patients (26,000 in the past 30 years) about alternative and complementary therapies even when all hope seems lost. She spends half her time educating patients about cancer prevention – prevention in the US (largely early dectection), she says, being, an “obscene masquerade” of what it should be – and the other half discussing patients’ options.

She says her service is “individualised and patient-driven, as opposed to mostmedicine, which is protocol-driven”.

She says that she is most optimistic when a patient “is looking to repair every organ, system and gland in the body without interfering with toxic treatments” – in other words, seeks to avoid chemo or radiation (but she also works with patients taking those therapies) – she recognises that she is not a doctor and does not tell patients what to do. She says that her centre doesn’t charge for its service, and relies on charitable donations to survive.

In a few cases, Susan says, she has tried to dissuade patients from strictly following alternative therapies. She tells the story of one patient who had a large breast tumour, and who wished only to pursue alternative treatment.

“I told her: ‘You have a growing tumour that you’ve been ignoring for a long time. If you agree to have some surgery, you will debulk most of the disease in a matter of hours and give your immune system a chance to fight off the rest with our help.’

“And she fought me and fought me and fought me. By the time she realised that this thing had eaten up most of her breast, it was too late for my advice to be valuable, because they couldn’t operate any more. And she died.”

Part of the problem, though, is that alternative therapy and conventional medicine have grown so far apart that, for many patients, one side’s rhetoric is all they hear.

Probably the longest-running controversy is that surrounding the Gerson therapy, a nutrition-based approach to cancer developed by Dr Max Gerson, a German immigrant to the US, in the 1950s.

Although Gerson died in 1959, his legacy continues in the form of the Gerson Institute, run by his now 83-year-old daughter, Charlotte. Patients still travel to the clinic in Tijuana, Mexico, where treatment costs $5,500 a week; although they may also, if supported by a Gerson-trained carer, pursue the therapy at home at lower cost.

Gerson therapy involves a tough nutritional regime – 13 glasses of juiced organic fruit and vegetables per day – plus coffee enemas and liver enzyme pills. Gerson believed that while the fruit and vegetables replenished the body’s nutrients, the enemas helped the body to excrete cancer-causing toxins; although other experts have questioned his claims. As for the liver enzyme pills, they replace juiced calves’ liver – discontinued in 1989, after bacterial contamination was thought to have led to the deaths of several patients a decade before.

Carla Shuford, from North Carolina, is a surviving patient of Max himself. In 1958, aged 15, she was diagnosed with an osteogenic sarcoma, or bone cancer, in her leg, which had spread to her lymph system. She visited the Sloan-Kettering cancer centre in New York, where doctors told her they could buy her six more months by amputating her leg from the hip.

Even as she was having the amputation, her mother was visiting Dr Gerson in his New York offices. There she bought a juicer, with which she would begin the therapy at home.

Caring for Carla soon became a full-time job. “It was so laborious,” she says, “because the juicer in that day was like a huge carjack. It was very heavy-duty, because you didn’t want any air to come in. You would take the stuff like the carrots and put it sort of in a burlap cloth, and put that in what he called a presser, and pressed the juice out of it.”

So many organic vegetables were needed that the Shufords began assigning local farmers to supply different products for the regime – one would provide the carrots, another the lettuce, and so on.

“It took a crate of lettuce every day to get the juice from it. So the whole community became involved in our recovery.”

Getting the fresh organic calves’ liver was even more of a struggle. “We located a place in Ashville, about 40 miles from where we lived, and my father would meet the bus every day and pick up the calves’ liver that would arrive that afternoon, that my mother would juice because it couldn’t be frozen.

“I’ll never forget drinking the liver juice. It literally was drinking blood.

“While other children went and played outside, and went to the drug store and had Cherry Cokes, I was going home to liver juice.”

For a long time, Carla’s prognosis remained grim; doctors regularly X-rayed her lungs, as her type of cancer normally metastasised there. But in fact the reverse happened. Slowly, the cancer disappeared from her body: and she has now outlived her hospital’s 30-year follow-up survey.

To this day, Carla lives on a diet of organic fruit, vegetables and whole grains.

She remains adamant that Max Gerson saved her life – though she admits that she “cannot absolutely 100% prove that it was the Gerson diet that worked”.

And there lies the problem. Most doctors would look at the fact that Gerson therapy has not been proved effective, and conclude it was a spontaneous remission.

Today, Carla is a healthy 62-year-old who swims a mile every morning, and looks extraordinarily well for her age – other than, she says, the wear and tear that comes with spending 48 years on crutches.

Charlotte Gerson, for her part, remains resolutely opposed to the medical establishment, for not giving credence to her father’s views.

“We’re not in a free country; we’re living in a medical dictatorship,” she says.

“The public is becoming more and more aware that doctors are not helping them. They drug them and drug them and they get worse and worse, and sicker and sicker, and in cancer particularly they drug them to death and they get miserable and suffer and die in agony.”

Gerson’s opinions are undoubtedly strident: she believes western drugs are fundamentally “toxic”, and therefore of no use in cancer treatment. Many doctors, on the other hand, reckon treatments such as the Gerson therapy offer false hope. Is there any chance of common ground? Perhaps.

“Both sides are a problem,” says Dr Siegel. “I read a lot of the alternative stuff.

They’re almost as bad as doctors, some of the organisations: ‘Doctors are terrible, don’t have radiation, don’t have an operation, they’re mean and cruel and lie to you and just making money.’ So it’s hard to get together with people like that.

“There are times I will write to some of these alternative groups and say, you know you’re getting a little extreme in what you’re telling people.”

With regard to Gerson therapy, he adds: “What we need to do is sit down with the Gersons; instead of having conflict and saying this is crazy, saying, all right, let’s do a controlled study. Let us see.”

Partly thanks to the integrative therapy movement, indeed, clinical trials into the effects of some alternative therapies are under way.

In the US, for the Gonzalez regimen – a complex therapy involving pancreatic enzymes, diets, supplements and, yes, extracts of animal organs – one statistically insignificant study has shown superior survival rates for patients with pancreatic cancer; a larger study is under way. Two studies into shark’s cartilage are continuing. On the other hand, studies into Laetrile found little evidence of effectiveness against cancer.

In Texas, Dr Burzynski is recruiting patients for no fewer than 32 trials into the efficacy of antineoplastons in cancer, and has agreed not to treat patients unless it is part of a clinical trial.

Dr Rosenthal, for his part, suggests the increased study of herbs could be a fruitful area. “A lot of these therapies that we’re talking about – herbs, botanicals – have been used for centuries. Where do our best chemotherapeutic agents come from? They come from plants, they come from boxer trees – so some of the things people are really trying to do now is answer the questions about standardisation of botanicals and herbs.”

The “deconstruction” of herbs – that is, working out what chemicals go to make up a traditional alternative remedy – is, he says, a major area of research.

Dr Siegel, for his part, would welcome more research into the relationship between the mind and the body – and the impact that faith, and belief systems, might have on a patient’s care.

“I always say, quantum physicists and astronomers do not have a problem with what they don’t understand. The universe is beyond our explanation, but we don’t question life.

“If I had the money, we wouldn’t be in outer space – we’d be in inner space.

To say” – he taps his head – “what the hell’s going on in here? This intelligence,

wisdom, how does it manage? It’s an amazing thing. If that awe were part of

medical education, we’d see more things happening.”

Bob Gilley would concur. “The only thing about me that was special was the belief system,” he says. “I believed I could do it. It’s amazing what human beings can do if they believe.”

Not all patients are as plucky as Bob Gilley. But if alternative therapists and medical science can work more closely together, perhaps it won’t take another three decades of research to give people with advanced cancer the hope they need.

THE MOMENT THAT CHANGED MY LIFE

In December 1984 Greg Anderson, a “big church” organiser in California, was diagnosed with the biggest cancer killer of them all – stage IV lung cancer, which had spread through his lymph system – and told he had just 30 days to live.

He had already had one lung removed; now, his doctor said, the “tiger was out of the cage”; his cancer had come “roaring back”. Effectively, it was a death sentence.

Then came an incident that was to change Greg’s life: a moment spent watching his two-year-old daughter playing on the living room floor.

“I remember feeling one of those moments of fear and sadness and despair, all mixed together,” he says.“I thought, I’m not going to see her grow up.

“I remember getting out of my chair, and just filling up with tears, and running to the bathroom, and just weeping.”

Paralysed with fear, Greg made a desperate prayer to God for help – a prayer he believes was answered with a subtle change in his thinking, as he began to work out what he needed to do to survive.

First, Greg sought out survivors to learn how they had beaten cancer. Through them, he turned to Dr Carl Simonton, the mind-body therapist who treated Bob Gilley – and, remarkably, beat his cancer. He has now been clear of cancer for almost 20 years.

Greg can’t conclusively show that it was the alternative therapy that cured him. He had also had his lung removed, and went through radiotherapy – although the chances of beating stage IV lung cancer, with or without chemo, were always slight.

But he believes his decision to dig deep, and to think positively about survival – together with a strict vegetarian diet – was the key.

Deciding to forgive others, he says, was another important turning point, as he let go of feelings of resentment he had built up over the years. These days, as head of an organisation called the Cancer Recovery Foundation of America, Greg has published books on developing what he says are the attitudes necessary to recover from cancer: among them taking control of your treatment programme, putting faith in it, and developing spiritually as you go through the process. To sum it up in Hollywood terms: you need to believe.

Cancer changed his life so much that, looking back, Greg thinks the negative responses he felt were almost from a different person. “That was a whole self-pity issue, and not very productive.”

Underneath it all, though, he’s still human.

“You have days when you doubt. I was in so much pain at one point that in one moment I was afraid I was going to die, and the next I was afraid I wouldn’t die. I can only say that my basic faith in God pulled me through.”

“I give patients my sermon – do you want to be a survivor?” he says. “Statistics don’t apply to individuals.

”