LIVING ON A KNIFE EDGE

©TOM BIBLE2007

5,500 WORDS

TOM BIBLE

21 PHOTOS

OVERVIEW

“Five years ago Tom Bible was diagnosed as having a rare and inoperable tumour deep in his brain. In this harrowing memoir, he recalls his quest to find a surgeon prepared to accept the challenge of operating on him- and how one man’s extraordinary skill with a scalpel (and tube of superglue!) saved his life.”

(Observer Magazine, 25th January 2004)

LIVING ON A KNIFE EDGE

Things were not going well for me in the summer of 1999. I was 32 years old, and while I was starting to find my feet in my new career as a photojournalist, I was living in the wake of two bad relationship break-ups and I had recently gone into therapy to help me deal with feelings of low self-esteem and a general lack of confidence.

The one thing I thought I had, though, was my physical health. In my twenties, I’d been a heavy drinker and smoker, but I’d long since cut back on both of these. I was eating well and exercising. I had just cancelled my private health insurance because it seemed to be a bit of a waste of money.

Then on the morning of 7 July, I got a headache. This was not a normal headache. It was the pounding, throbbing, mother-of-all-headaches with an intense pain behind my eyes. It was unlike anything I’d had before. Nothing could shift it. And something strange was happening to my vision. I’d look at the floor and it was as if bubbles were rising from it. I’d have the same mini-hallucination over and over again whenever looking at a flat surface.

I did what anybody would do in the circumstances. I ignored it. I simply assumed that it would go away.

This carried on for seven weeks. I was just about surviving when, one afternoon, I was playing hide and seek with my four-year-old niece. Suddenly, I felt the most incredible pain and pressure inside my head, and then I went blind. The blindness didn’t last long – a minute, perhaps, or maybe two. But it scared the life out of me.

My doctor very quickly established that something was seriously wrong with me, but it took 18 months, two neuro-ophthalmologists, four neurologists, one lumbar puncture (involves sticking a 4 inch needle into the spine to measure inter cranial pressure) and six different sets of MRI scans before anyone realised exactly what it was: a particularly unusual brain tumour that would eventually kill me if nothing was done about it.

My first set of scans showed a grey mass located inside my superior sagittal sinus (‘the sinus’), the main vein through which all blood flows out of the brain. The specialists said they had never seen anything like it before and didn’t know what it was. Then one neuro-ophthalmologist became convinced that it was a blood clot that had formed inside this critical vein, so I was put on Warfarin, a blood thinner, and Diamox (normally prescribed for epilepsy or glaucoma) to lower the inter-cranial pressure. I was to be scanned at six-monthly intervals in the hope that the blood clot would slowly dissolve.

On 12 December 2000, I had the first scan at the Royal Free Hospital in north London. I went with my then girlfriend, Jessie. We had been seeing each other on and off for a year, and while there had been a few break-ups along the way, we had decided, in November, to commit to the relationship. By now, the headaches had almost disappeared and my eyesight had returned to normal. I was expecting to be told that the blood clot had gone, that I was back to normal.

I couldn’t have been more wrong.

I knew something wasn’t quite right when they told me that they wanted to do a second scan with a contrast dye so they could get a clearer view of the veins in the brain. After this second scan, I was ushered into a room with Brian Kendall, a neuro-radiologist. He showed me the grey mass on the MRI displayed on the wall lightbox and how the mass had grown through the sinus and was now growing on the outside of the vein. ‘It isn’t a blood clot after all,’ he said. ‘It’s a brain tumour growing inside your sinus. I’ve never seen this before, it’s highly unusual.’

A few days later, at Princess Margaret Hospital in Windsor, I learned more about my tumour from Neurologist Davyd Thomas. It was a benign meningioma and it was potentially fatal. If it wasn’t removed through surgery or shrunk by radiation, it would continue to grow up my sinus and I would die. Given my (relatively young) age, he felt it would be best to remove it surgically.

He said I would most probably also require radiation after the surgery, as it would be impossible to remove the area of the tumour that had grown through the sinus.

As tumours go, benign meningiomas are at the low end of the risk scale. Removing a meningioma is normally considered the ‘tonsillectomy’ of neurosurgery.

But my meningioma was different. Normally, this type of tumour grows on the outside of the sinus. Mine, however, had grown through the vein wall and was growing up it. This made it incredibly difficult to operate on and remove. The blood flows through the sinus at a rate of a litre a minute. So if a surgeon were to cut into the sinus or one of the surrounding veins while trying to remove the tumour, the resulting haemorrhaging could easily result in a stroke, and possibly death.

I now had a challenge: to find a neurosurgeon who was both willing and able to remove my tumour. Dr Thomas recommended two vascular neurosurgeons in the UK. I arranged an appointment with the first one, who subsequently cancelled, saying that it was not the type of operation he would perform. I visited the second neurosurgeon at the National Hospital in London – the leading UK neurosurgery hospital (and one of the most highly rated in the world). He said he had only heard of one of these before. They had had to remove it by resorting to a practice called the ‘cardiac standstill’. In this, they stop the patient’s heart, drain the blood from the body and reconstruct the tumour-infested sinus area, pump the blood back into the body and kick-start the heart again. He also said he had never performed this type of operation but he felt he could get a positive outcome with an alternative. This was encouraging, but I was nervous about letting someone carry out an operation as complex as this for the first time on me.

It was a very challenging time. I fluctuated from feeling paralysed with fear to feeling determined and full of resolve to find the best neurosurgeon. I gorged on information, scanning the internet for anything I could find, speaking to friends, family and frankly anyone I thought might be able to help me. There was too much to take in: about tumours, about my tumour, about neurosurgery and neurosurgeons.

Jessie was fantastic. She is a lawyer, with a brilliant, analytical mind, and is an excellent listener. She could soak up all the information that was thrown at me by the net, by friends, family and doctors, and give it clarity and structure.

The other great pillar of strength I drew on was my faith in God. In my teens, while studying at a Jesuit school, I met David Barlow, who was rather like Robin Williams’s character in Dead Poets Society – a maverick and an inspiration to many of us at school. He gave me an insight into the divine that went beyond the ceremony of religion: an inner dialogue which was incredibly powerful. For many years, these lessons had remained at the back of my mind, but for the past few years I had been rediscovering my sense of spirituality and started to experiment with Western Buddhism and transcendental meditation. Now, I returned to the lessons David had taught us.

If you had told me in my twenties that I would resort to prayer or spiritual healing, I would have laughed. But both these sources had given me phenomenal strength, a strength I needed right now.

Why did I have a tumour? There was no good reason, and there still isn’t. In fact, for all the spectacular leaps in neuroscience in the past century, no one really knows why people develop brain tumours.

The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York says there are only two known environmental risks for brain cancer: exposure to X-rays for the purpose of treating cancer (which, you have to admit, is rather ironic) and any history of disorder to your immune system.

There are a number of factors that make you more likely to have a brain tumour, including being male, being white and being over 70 (I fitted two out of three of these). But even this isn’t true of all tumours. Meningiomas are more common among women.

After Christmas, I continued my search for neurosurgeons. My parents were encouraging me to consult neurosurgeons in the US. At first I resisted this option, mostly because I wanted to take the easy option and find somebody on my own doorstep. But the more I researched and spoke to friends who worked within the NHS, the more it became clear that neurosurgery in this country is severely underfunded.

There are undoubtedly some brilliant neurosurgeons in the UK. However, exorbitant US hospital fees allow neurosurgeons to have the very best resources, hospital facilities, staff and technology at their disposal – and more importantly, the large population base over there allows neurosurgeons to specialise in a way that isn’t possible here. I wanted to find the guy who had performed the procedure I required as many times as possible with the best possible outcomes.

In one respect, at least, I was lucky. While my earnings as a photojournalist couldn’t cover the cost of an operation, my parents, fortunately, could and would foot the bill. And so we went on a whistle-stop tour of the US to find my neurosurgeon.

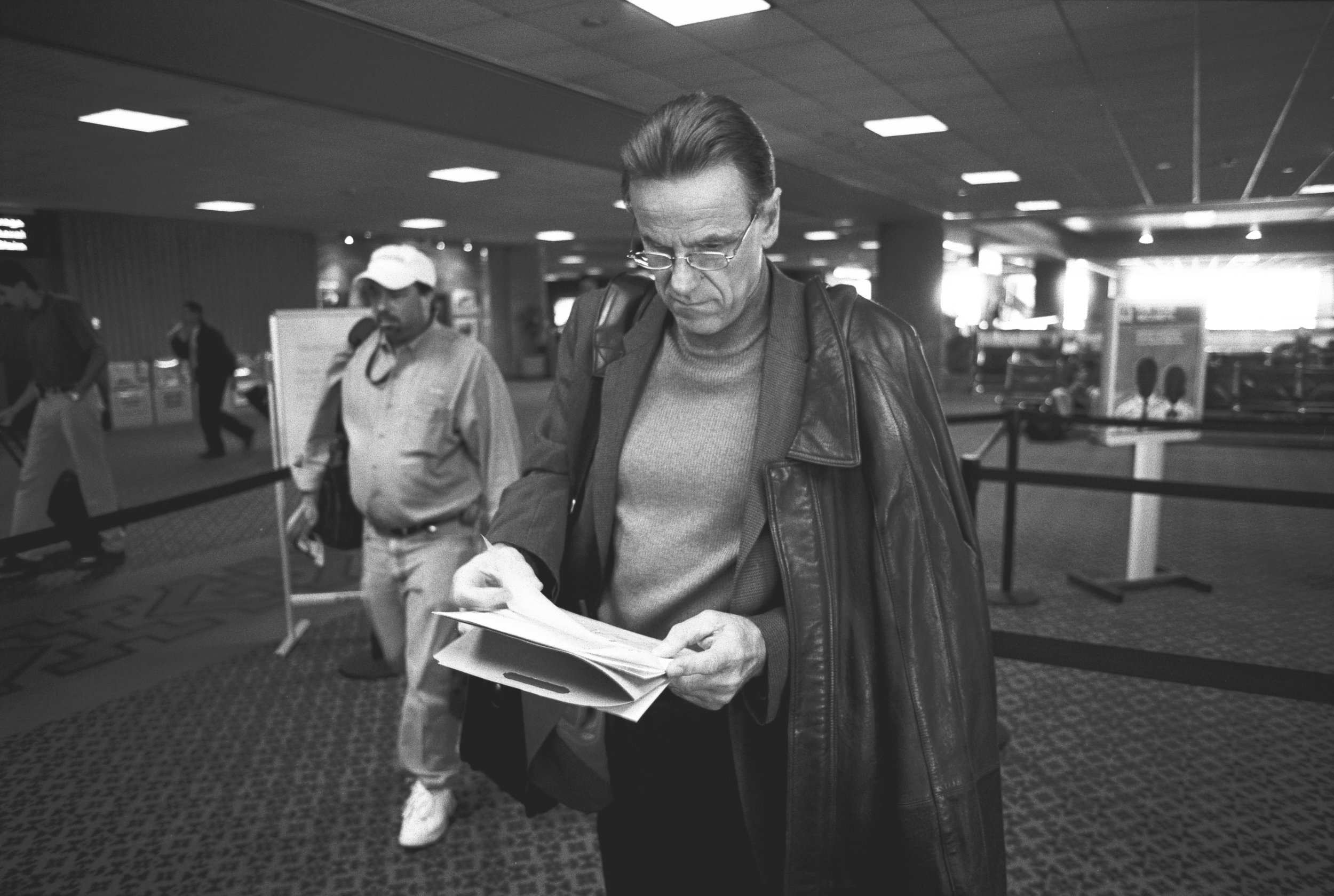

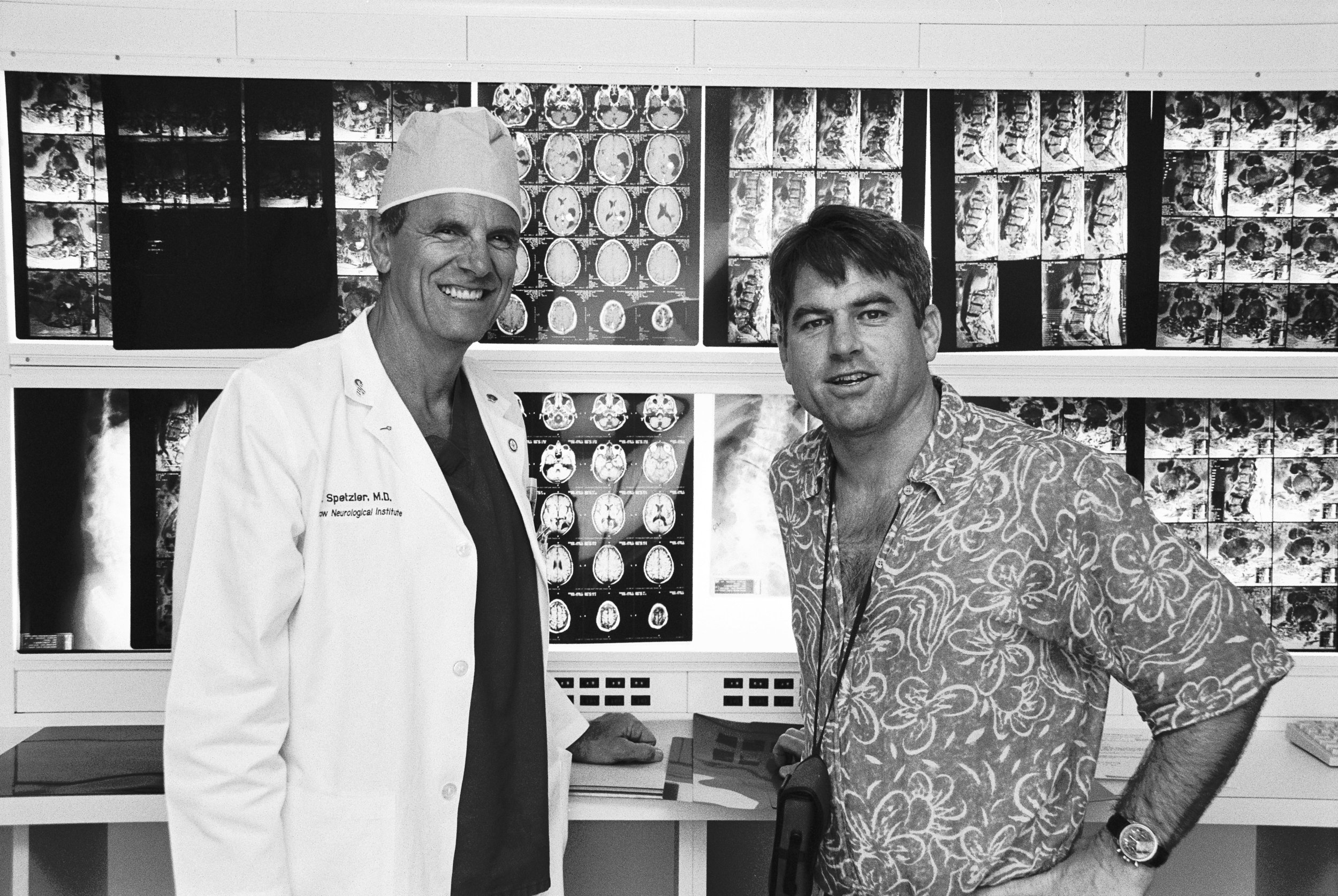

Little more than six weeks after I was diagnosed, I arrived at the Barrow Neurological Institute (BNI) in Phoenix, Arizona, to meet the man who would ultimately save my life, Dr Robert Spetzler.

The BNI is one of the world’s neurological powerhouses. In 2004 it operated on over 4,000 patients with its eight dedicated operating rooms – twice as many patients operated on by the National Hospital in London.

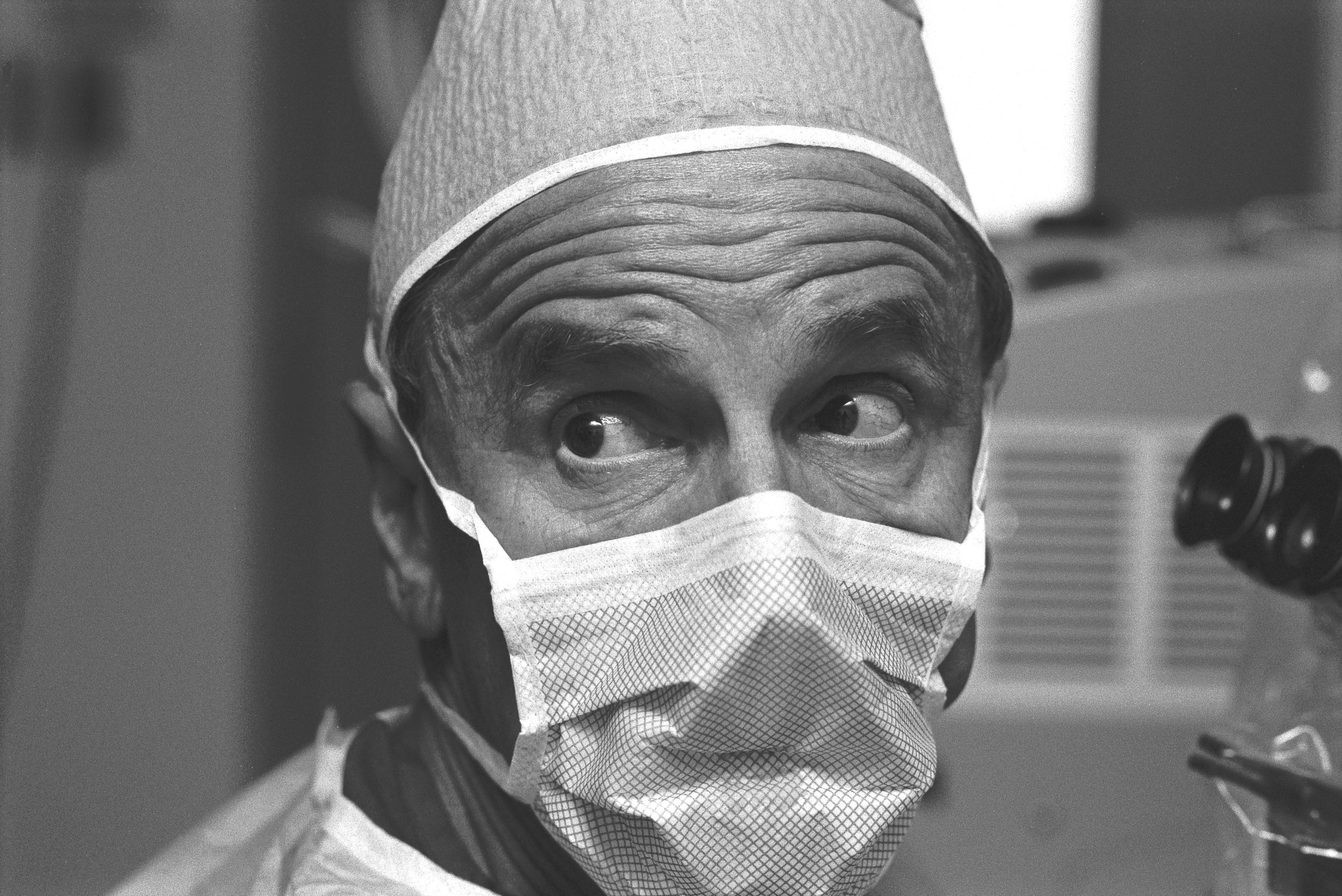

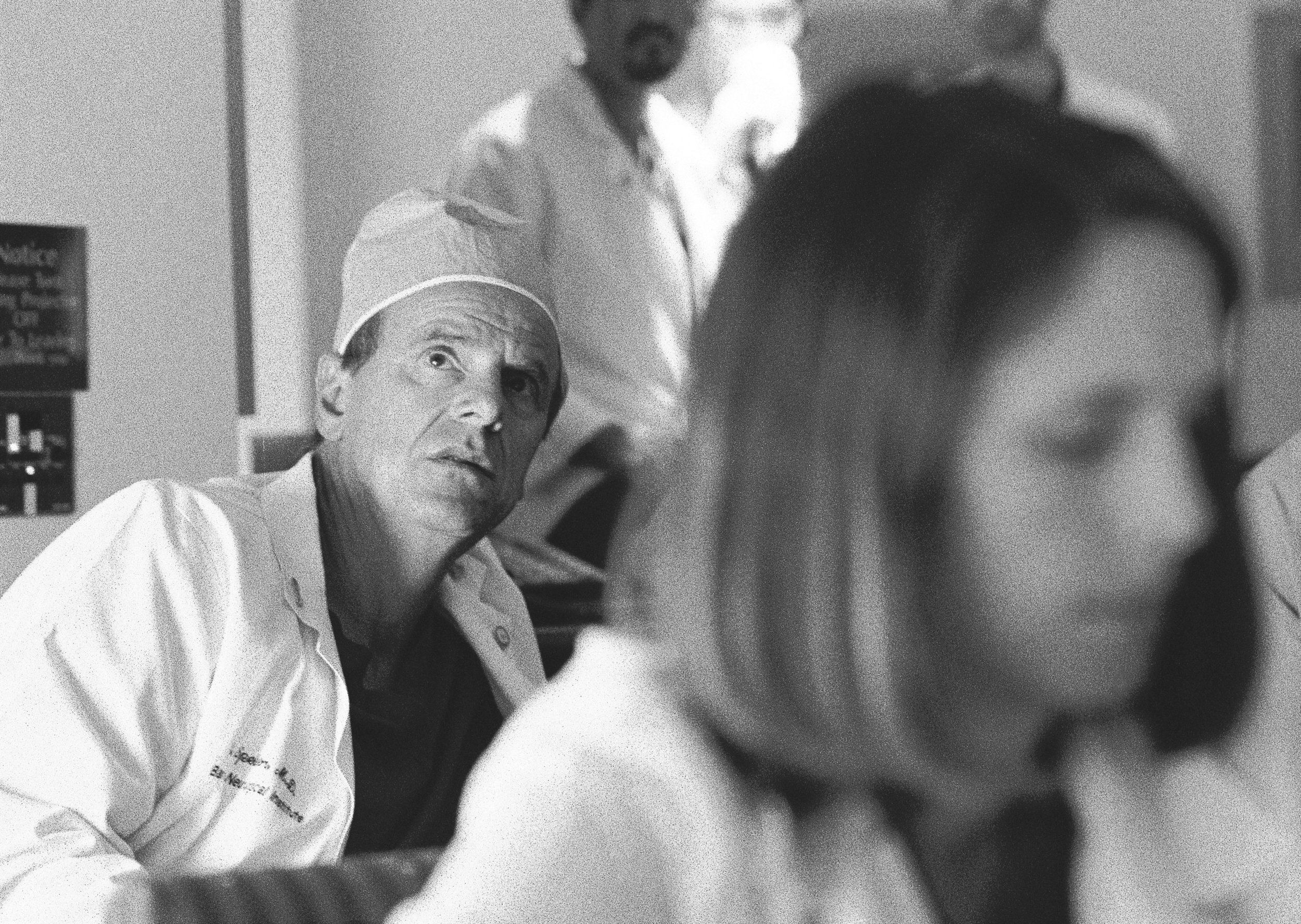

I was ushered into a small, basic room, slightly bigger than a cubicle. A young doctor asked my details. Then Dr Robert Spetzler arrived. He was dressed for the operating theatre and clearly busy.

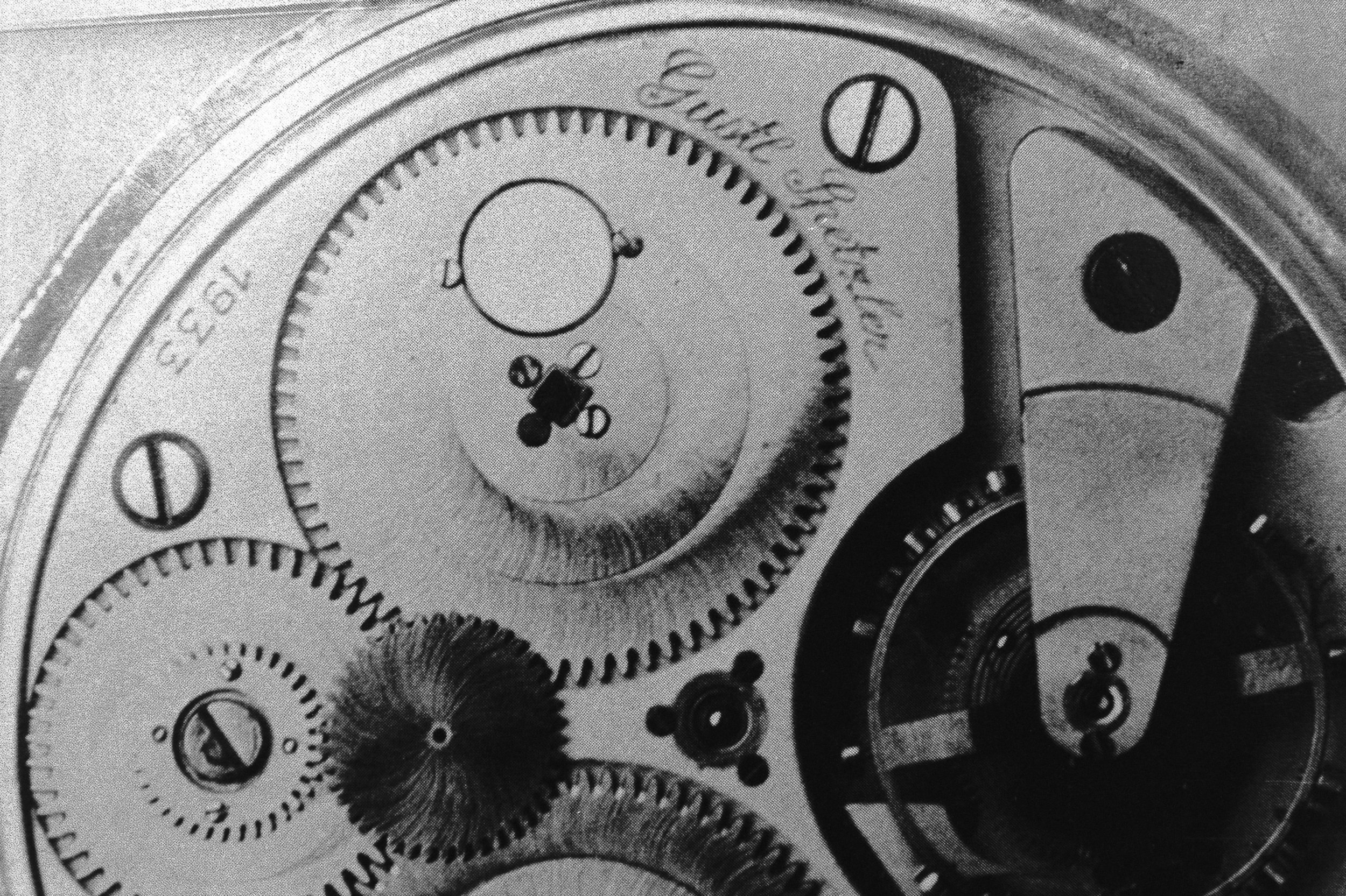

Robert Spetzler was born in Würzburg, Germany in 1944. At the age of five he stood on a rusty nail and contracted tetanus, and would have died had it not been for a mysterious new drug called penicillin. His father was August Spetzler, the ‘father’ of the quartz watch. His second cousin was killed for a suspected assassination attempt on Hitler.

When Robert was nine, the Spetzlers moved to America, near Chicago. He had a loving but strict upbringing (the children were not allowed to watch TV). He played the piano and excelled at music. He finished medical school in 1971 and did his training under three legends of neurosurgery, Paul Bucy in Chicago, Gazi Yasargil in Zurich, and Charlie Wilson in San Francisco. And he is now a legend in his own right, specialising in operations that others either won’t or can’t do.

Spetzler is an extreme skier, jumping out of helicopters to find the most challenging slopes. He mountain bikes on treacherous routes through Arizona’s rocky trails. He is phenomenally fit, something he believes is critical to his success.

He stresses to his trainees that to do a job as physically and mentally demanding as neurosurgery, they have to be in the very best shape. Some days they will be operating for seven hours at a time. To do this and be able to keep their hands steady 6in inside someone’s head takes a degree of stamina and concentration that most of us can barely imagine.

‘We’ve examined your films very closely,’ Spetzler said to me. ‘We’ve only seen one of these before, but we think yours is different.’

‘What would your approach be?’

‘I’ll make a large opening at the back of your head, take a good look around, and then I’ll make a decision.’

‘Does that mean you would be performing the operation?’

‘Yes it does.’

As two of the surgeons I had already seen had turned me down, I was afraid that Spetzler might do the same. That simple ‘Yes it does’ was the best news I had had since my diagnosis.

I had a sheet of 30 questions that I asked all the neurosurgeons. ‘What would you do if the surrounding veins are caught in the tumour?’

‘I’ll make that decision when I get in there.’

‘What are the risks associated with the operation?’

‘There’s a 5 per cent risk of complication, which includes infection, loss of mobility in your legs and arms, or death.’

‘How many of these have you operated on before?’

‘I’ve operated on 100 patients in and around the sinus area.’

This was the key bit of information I had been looking for. I wanted to find the guy who had performed the most operations of this nature. Bizarrely, I didn’t ask my next stock question relating to his percentage of successful outcomes. His body language answered the question for me. He was relaxed and in complete control. He refused to be drawn into making assumptions. ‘I’m a realist,’ he said, ‘neither an optimist nor a pessimist.’

When I had bombarded other neurosurgeons with these questions, some had understandably become defensive, but Spetzler didn’t mind me asking him all of them – in fact he really welcomed them, and I sensed he probably wanted them to be as awkward as possible. At the same time I felt apologetic about taking up his time.

‘I’m sorry if I’m being anal with all the questions.’

‘You have every right to be anal at this point in your life.’

We both laughed, and it was at this moment that I realised that Spetzler was my man. After the meeting, just as I had done after every meeting, I wrote down detailed notes.

‘Very impressive. Very honest,’ I scribbled. ‘I liked his wise approach of taking one step at a time. I felt very good; he gave off a massive aura of confidence… Refused to be drawn into making assumptions… Very firm, relaxed, fresh-looking, cool, in control… Not the type to be rushed, but would think things through calmly and methodically.’

I also wrote down his final words to me: ‘This is something you’re going to have to learn to live with for the rest of your life.’

Spetzler’s diagnosis cheered me up, but my search wasn’t over. I was on my way to see two more world-class neurosurgeons. Charlie Wilson, chairman of neurosurgery at University of California in San Francisco was widely regarded as the best neurosurgeon of his generation. Now in his early seventies and close to retirement, he had trained Spetzler. Like Spetzler he was a fireball of energy, running 80 miles a week, playing competitive tennis with Rod Laver and writing over 600 academic articles. He was written about by Malcolm Gladwell in his 1999 New Yorker essay ‘Physical Genius’.

‘Neurosurgery,’ Gladwell wrote, ‘is thought to attract the most gifted and driven of medical-school graduates. Even in that rarefied world, however, there are surgeons who are superstars and surgeons who are merely very good. Charlie Wilson is one of the superstars. Those who trained with him say that if you showed them a dozen videotapes of different neurosurgeons in action – with the camera focused just on the hands of the surgeon and the movements of the instruments – they could pick Wilson out in an instant. He has a distinctive fluidity and grace.’ Wilson took a long look at my films. ‘I wouldn’t go into the sinus. It’s just too dangerous. It’s a high-risk operation.’ He said he would prefer to do a biopsy to ensure that it was a benign meningioma, then put me on a five-week course of daily radiation. This brought with it less risk than surgery, but he felt it would have the same result.

Wilson’s argument was very convincing and one that my parents favoured, but I wasn’t convinced. It contradicted the research I had done which showed that the smaller the tumour mass, the more effective the radiation. I wanted to have as much of the tumour cut out as possible. Also, I was still young, and I didn’t want this ping pong-sized tumour lodged in my brain for the rest of my life.

The next day we went to Baltimore, Maryland, to see Donlin Long, who had run the department of neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital for 28 years. Another God-like figure of neurosurgery. Like Wilson, he felt that going into the sinus would be too risky. He felt that the wisest option was to remove the tumour on the outside of the sinus and then radiate the remainder in the sinus.

Four days; three of the world’s greatest neurosurgeons; three different opinions. And these in addition to the views I’d already received earlier on my trip and in the UK. After leaving Spetzler on Thursday, things seemed reasonably clear. By Monday, things were anything but.

Having the money to afford any treatment was a blessing. But what I needed now was the courage and clarity to make the right decision. On Monday evening I pulled out my notes from all my meetings with the neurosurgeons and began to reflect.

Spetzler had a reputation for getting results that other surgeons could not begin to contemplate. Some neurosurgeons might argue that Spetzler was too aggressive, but my research concluded that an aggressive approach delivered the lowest risk of recurrence (as long as the operation went well). This was a critical factor in the neurosurgery versus radiation equation. However, this was the biggest decision of my life and I needed to be sure that I was making the right choice.

On Wednesday, I called Spetzler’s office to book myself in for surgery. The operation was confirmed in three weeks’ time, on 2 March. I started running every other day and going to church most days. I had read a book on imagery called Getting Well Again by Dr Carl Simonton, so I began to do imagery exercises three times a day. I would visualise myself coming out of the operation strong and without any complication.

On 27 February, Jessie and I arrived in Phoenix and spent the next day settling in. I visited the hospital to give them a deposit. The operation, including the hospital and doctors’ fees, would cost an eye-watering $90,000.

I had completed a will a few weeks earlier just in case things didn’t work out. That night I also made a note of my personal details such as bank account numbers, accountant’s address, alarm code to my flat in London and left them with Jessie.

5.30am Thursday: I checked into the hospital. My surgery was booked for the following day at 11am. Before that there were lots of tests: cardiograms, lung X-rays and all sorts of blood tests. But first I had to have an angiogram.

The radiographer explained what this would involve. First, they would cut into my leg and insert a plastic catheter into the femoral artery in my groin. They would run it up my body into my head, where they would inject contrast dye to highlight all the blood vessels for the film. This would indicate whether or not the sinus was completely blocked.

‘Hang on, did you say you’re going into my artery?’

The doctor explained, with a slightly surprising calm, the risk of the catheter piercing my arterial wall causing me to suffer a stroke. This could result in neurological impairment or death. I was not prepared for such a blunt risk assessment. The reality of what I was about to go through began to kick in.

I was conscious during the procedure, and felt a warm sensation in my head as the dye swirled around my brain. I heard the camera snap away.

‘Is the sinus blocked?’

‘It’s too difficult to tell. Dr Spetzler will give you the results this evening.’

I was wheeled down to a room on the first floor where I had to remain horizontal for six hours to stop the incision in my artery from re-opening.

That evening Spetzler appeared in the doorway, followed by a posse of trainees. He seemed in a hurry, as if he was in a pre-operative zone. The angiogram indicated that it would be too dangerous to go into the sinus. Instead he would remove the tumour on the outside of the sinus and then radiate.

I was very disappointed. I was desperately hoping that he was going to completely remove the tumour. He asked me if I had any questions, then disappeared with his gang of trainees in tow.

I had my last food and drink before the operation: a cheeseburger and chips. I did my final set of imagery exercises and prayed for strength and courage. I also prayed hard that Spetzler would get the best result possible. That was all I could ask for. I dozed off at 10pm. And slept surprisingly well.

At 6am I was woken up for a brain scan. Back in my room, my parents and Jessie arrived. Three friends called to ask how I was, thinking I had already had the operation.

‘OK, it’s time,’ the nurse announced as she entered the room with a trolley. I took a couple of deep breaths. I felt a rush of adrenaline surge through my body. I was very scared and desperately trying not to show it. The only positive feeling I could find was the thought that I was also looking forward to putting the surgery behind me, that 20 months of uncertainty were about to end.

At the doors of the operating room, we were told to say our good-byes. We were aware these might be the last words we ever said to each other. My mother was carrying a small plastic bottle of holy water given to her by a friend. She sprinkled some on to my head. I hugged her and then Jessie.

Then I hugged my father. Our relationship had been through its ups and downs over the past few months – in fact, for the past few years. We said nothing, but a torrent of unspoken feelings between father and son were captured in one powerful embrace. We both had tears in our eyes.

Then the nurse took over. ‘How are you feeling?’

‘I’ve had better days.’

‘Do you know that you are going to have brain surgery, and are you aware of the risks involved?’

‘Yes I do, and I am.’

‘Do you wish to proceed?’

‘Yes, I do.’

I signed the consent form. Dr Steven Shedd appeared. He runs the neuro-anaesthesiology at the BNI and has played a key role in many of the 100 plus standstill procedures Spetzler has performed. He talked me through the procedure and then gradually administered 5mg of Midazolam, a Valium tranquilliser. I slowly drifted off, and was wheeled into the operating room for occipital-parietal craniotomy for a parasagittal meningioma at the hands of the director of the Barrow Neurological Institute, Dr Robert Spetzler.

‘Can you move your fingers for me?’ I open my eyes and see a blurry vision of Dr Shedd.

‘Good. Can you wiggle your toes?’

‘Open your eyes. Stick out your tongue.’

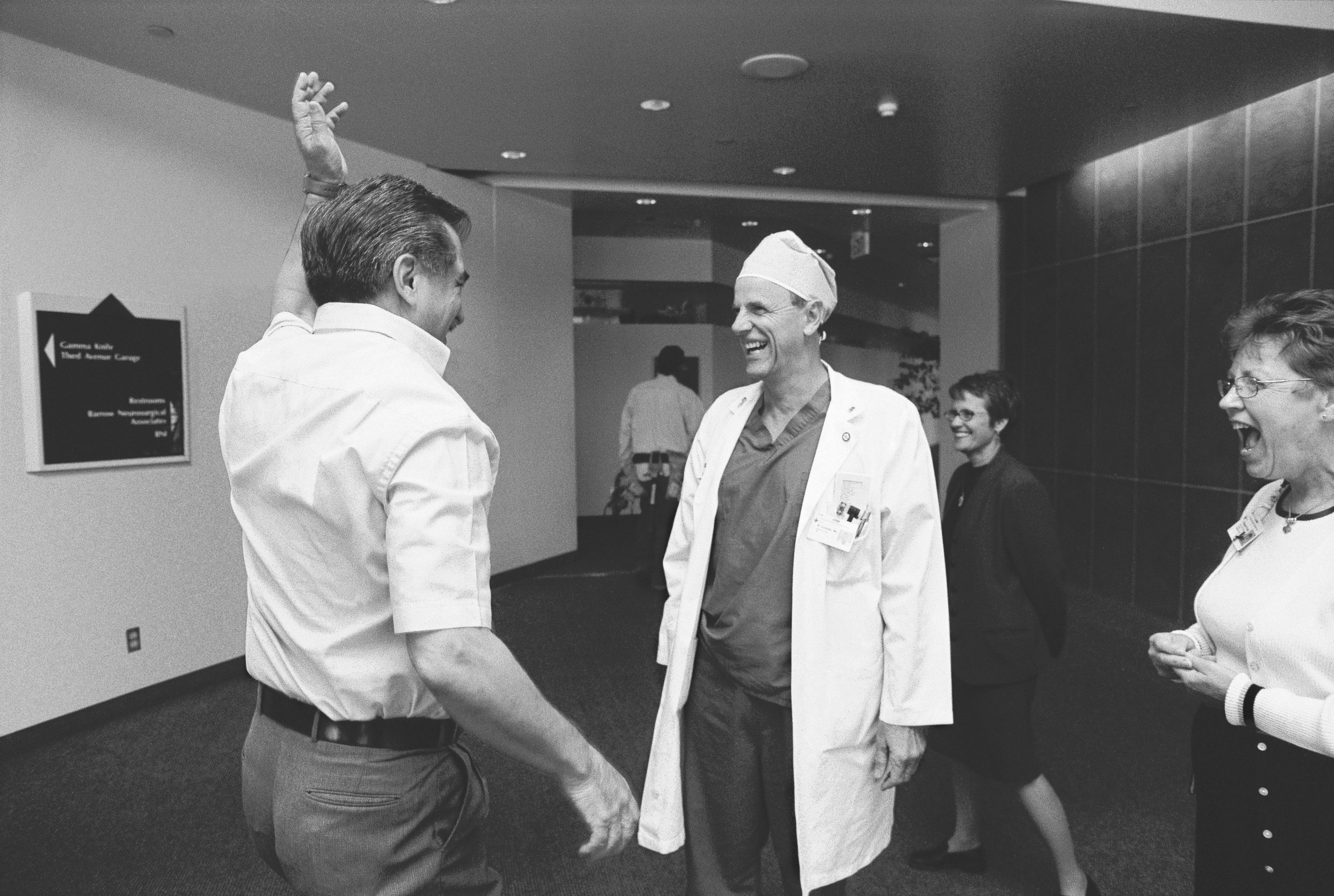

‘Excellent. You have just had brain surgery; you are in the recovery room. It went very well. Dr Spetzler went into the sinus and removed the majority of the tumour.’

What! How the hell did he do that! This was way too much information to process, I passed out again.

I woke up a few minutes later to find Jessie and my parents by my side. They told me that the surgery had taken four hours, two hours longer than anticipated.

‘Did they do a standstill?’ I asked them. Unconsciously I must have been processing Shedd’s ‘went into the sinus’ comment. Shedd then explained how Spetzler had made a large incision, how he had had a good look around, how he had realised that the majority of the tumour was located inside the sinus and how he had decided to go in to get it.

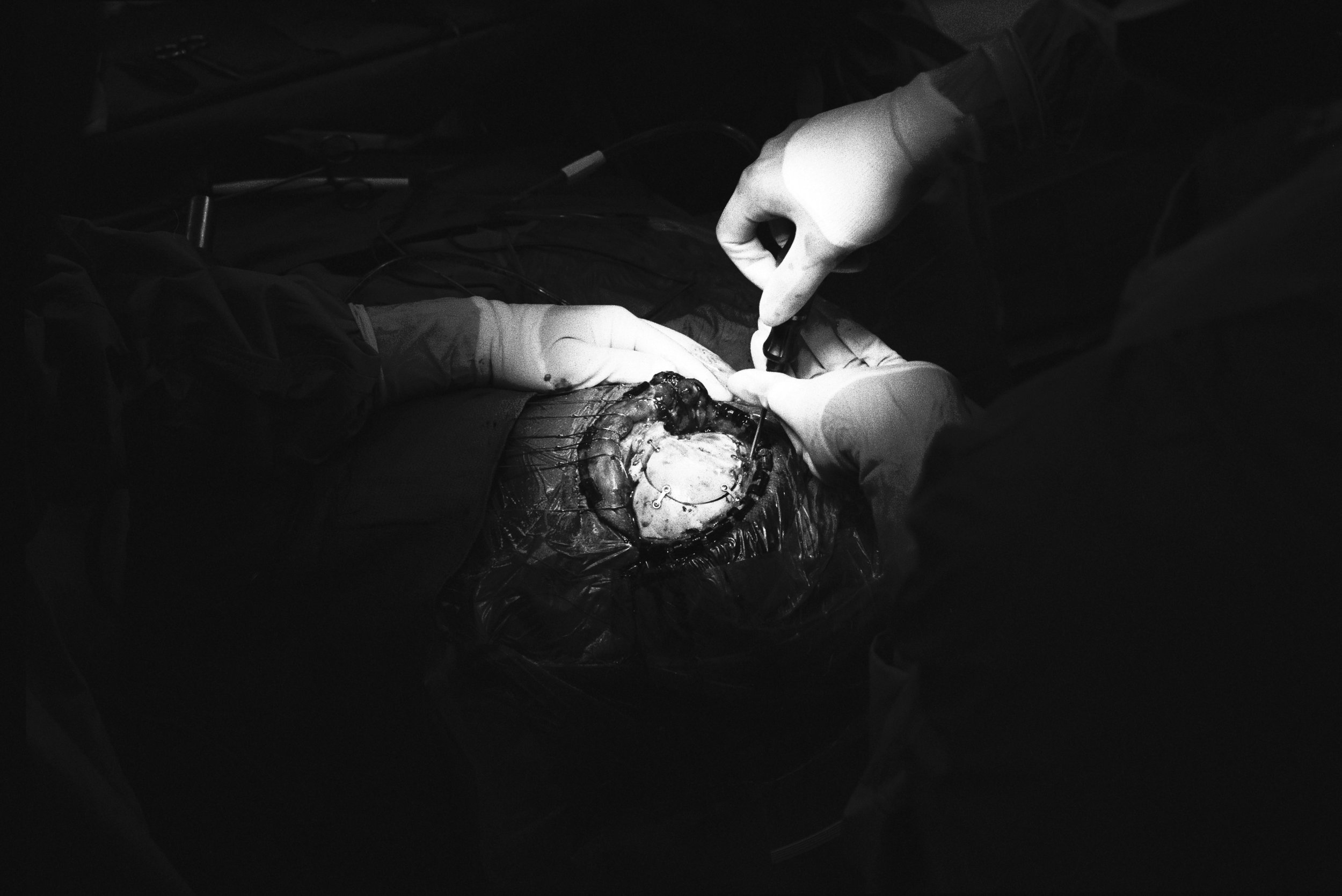

‘How did he do that?’ In all our meetings with neurosurgeons, nobody had mentioned this option. Shedd explained that the main reason neurosurgeons are nervous about going into the sinus is that it is incredibly difficult to control the bleeding once the sinus has been opened. Spetzler managed to control it with help from Shedd, who had increased or decreased my lung pressure with a mechanical ventilator to get my blood flow at just the right level. Too slow and the air would have been sucked back into my sinus, causing air bubbles to get into the blood system and creating an air embolus in my lung (often resulting in death); too fast and there would have been too much blood for Spetzler to see what was happening.

With the blood flowing at the right level, he went into my sinus with his scalpel to remove as much of the tumour as he could. His assistant then temporarily stopped the blood flow by pinching the sinus with his thumb while Spetzler cleaned up the blood. This process was then repeated over a 20-minute period.

This is the miracle of neurosurgery. A man with a scalpel inside the critical vein in my brain, trying to cut out a tumour the size of a golf ball, blood gushing out at up to a litre a minute, making it impossible to see what’s happening.

How could he be sure what he was cutting? He was partly helped by technology, but also by his innate ability.

Shedd explained: ‘Dr Spetzler’s got a tremendous ability to know what’s there without actually being able to see it… It’s probably his strongest attribute in his ability as a neurosurgeon: his ability to see in 3-D without really physically being able to see. It’s like an internal compass.’

I began to process the information. I was ecstatic. The combination of the unexpectedly positive outcome – and the large doses of morphine – caused me to go into a euphoric state. I started cracking very lame jokes and flirting with the nurses. None of them paid any attention.

My next stop was intensive care, where I had tubes everywhere in my body: my nose, my neck, my arms, my hands and my urethra. The most painful and most important of these was the one in the jugular artery in the neck which monitored my arterial blood pressure. They had super glued my sinus back together where they made the incision, but there was a risk that it might either re-open or that the blood clotting around the wound might spread up into the sinus. Both outcomes would have had devastating consequences.

I had an uncomfortable night’s sleep wrestling with the tubes protruding from my body. Even the pillow had become my enemy. My spirits were lifted by the numerous phone calls relayed by the nurse throughout the night from friends in the UK.

It was morning, and Spetzler pulled back the curtain. The miracle worker. ‘How are you feeling?’ He was smiling and relaxed. I thanked him profusely. It is difficult to know what to say to the man who has just saved your life. I wanted to hug him, but it was too painful to move.

‘It went very well, but we had to leave some of the tumour in the wall of the sinus. It is very important that you receive gamma knife treatment as soon as possible.’

There was urgency in his voice. It was clearly not over yet. I knew all about gamma knife treatment. It is a technique to shrink a tumour by focusing a mass of gamma radiation on to a single spot inside the brain.

While you are under anaesthetic, a metal frame is screwed into your head. Then a massive brushed-metal helmet is fitted on to the frame. On the helmet are 201 holes. You are then taken into a dome-shaped reactor, where they shower gamma rays at your head. These rays can only penetrate the helmet through the 201 holes, which are positioned in such a way that the rays all meet at one spot, acting like an invisible scalpel.

As the tissue surrounding the tumour had to settle from my operation, I had to wait another week for this particular delight.

That morning I was moved out of intensive care. The first 48 hours after surgery are critical. I had met someone a few weeks earlier who had had a successful operation, but had developed an infection on his brain. He ended up spending four weeks in intensive care and lost partial mobility in his legs.

Blood pressure and body temperature were the most important tests for whether there was any infection, and on Saturday evening, the nurse checked my temperature. It was 101.4F. Too high.

‘Be careful now,’ she said. I closed my eyes and prayed for strength. I find this hard to explain now, but at the time I experienced this incredible feeling of love around me, as if all my family and friends were in the room supporting me. I could almost physically feel my immune system kicking into gear.

Two hours later my temperature had dropped to 99.1F.

The following day Dr Kris Smith appeared to discuss the radiation treatment. The tumour remaining in the sinus wall was about 1cm squared. If left untreated, the risk of recurrence would be very high; if treated with gamma knife radiation, the risk of recurrence would be only 5 per cent.

Three days after the operation, still on high doses of steroids to reduce the swelling of my brain, I checked out of the hospital. I could walk around, but not too far. On a couple of occasions I did too much and experienced the mother of all headaches. I spent the whole week eating and sleeping, and then I was back for gamma knife radiation.

After a mild dose of anaesthesia, I woke up with the metal frame drilled into my skull. It felt very bizarre to have my head trapped within this metal contraption. I was wheeled down to the gamma knife room. I lay down on the conveyor belt that carried me into the reactor. The helmet was attached to my metal frame. Smith left the room with his staff to plot the co-ordinates for all the rays next door.

Ready? The machine buzzed intermittently as it zapped the rogue cells lodged inside my sinus. It was all over in 50 minutes. I was kept under observation for six hours to ensure that there were no complications.

There was still a small amount of tumour remaining in the wall of my sinus, but it was much better than we had hoped. The next morning, we flew to New York.

Two months later, I was back in London, putting my life back together again.

It’s now nearly five years later, and I have just flown back from the US after getting my annual check-up from Spetzler. It was good news. The remaining lesion in my sinus wall is still there, but it has shrunk slightly since last year’s scan.

But this is not the end of it. I will still need checkups every year. It can still grow back.I’m no longer with Jessie. From the beginning, our relationship had been overshadowed by my illness. It’s incredible to go through all that with someone; and once you’ve been through it, you do feel you should be together forever. But as things slowly got back together in my life, it just wasn’t working out between us. We split up in June 2002.

This summer it will be 8 years since my symptoms first appeared. Materially, my life is similar: I have the same job, the same flat and the same friends. But everything else – my priorities, my perspectives on life, my view of myself, and my relationship with my family – has changed. For the better. I feel more grounded and, overall, happier than at any time in my adult life.

To me, this sense of happiness isn’t a luxury or something to feel smug about. It is a vital part of my healing process. As a result of exploring the spiritual side of my life, visiting various healers and reading widely, I believe there is a direct correlation between our emotional well-being and our physical health.

So I pray. I spend time with people I love and who make me feel good. It might not be the ultimate answer, but it is the route I’ve chosen, and so far, it seems to be working.

“‘I’m sorry if I’m being anal with all the questions.’

‘You have every right to be anal at this point in your life.’

We both laughed, and it was at this moment that I realised that Spetzler was my man. ”