INDIA 2.0

©TOM BIBLE2008

3,000 WORDS

35 PHOTOS

OVERVIEW

Billions of dollars are rolling into India’s booming dotcom industry - but in a country of a billion people, most can only dream of luxuries like internet access and mobile phones. Tom Bible meets the entrepreneurs who are hoping to change all that - by bringing technology to the masses, at a price ordinary Indians can afford.

INDIA 2.0

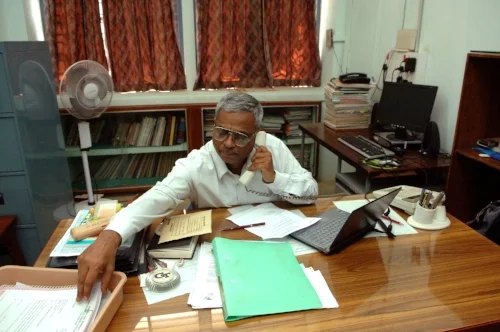

When you first meet Ashok Jhunjhunwala, professor of electrical engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology in Chennai, you don’t immediately get a sense of the passion of the man. Small-framed, with greying hair, he sits behind a neat desk in a spartan office in an ordinary university building. If it weren’t for the monkeys you can see wandering across the campus grounds, you could be anywhere in the world.

But Jhunjhunwala, a straight talker with an infectious enthusiasm, has a specifically Indian dream: to bring the power of technology to all Indians, from cities to rural areas, and so to create economic growth.

That, Jhunjhunwala says, means leaving behind the “master-servant” relationship he says India used to have with the developed world – and building a confident, outward-looking country which doesn’t only sell services abroad, but provides products and services to one of the biggest emerging technology markets in the world: Indians themselves.

And in a country with 600 million people living in rural areas – most of whom have little or no access to the internet – it means conquering India’s digital divide.

If Jhunjhunwala seems impatient, it’s easy to understand why. By way of explaining how far India has come, he tells me how, as a would-be entrepreneur, he returned to the country from a US university in 1981 – only to discover that he couldn’t get a phone when he wanted it. “I applied for a telephone, and it took me eight years to get a line,” he explains.

Now that India seems to be shrugging off the global crunch and is seeking to exploit its position as one of the world’s most rapidly emerging markets, it seems his country’s time has come.

Yet Indian growth is an “urban phenomenon”, Jhunjhunwala explains. “It is not happening in rural areas,” he says. “It’s a big challenge.”

And that’s why IIT Chennai has helped to incubate companies who aim to meet particularly Indian needs – from services companies who seek to bring employment to the rural India, to infrastructure firms such as wireless connectivity and cheaper PCs.

If Jhunjhunwala believes India-focused entrepreneurship is the answer, he doesn’t have to look far for examples. At Proto.in, a Silicon Valley style networking weekend for technology entrepreneurs, more than 60 fledgling companies have presented to venture capitalists and their peers, since the event started last year on the campus at IIT Chennai.

Part of the reason is the influx of venture capital over the past 4 or so years, which has given prospective entrepreneurs something to dream about. In November 2006, jobs website Naukri.com became the first internet company to go public in India, in a $500m IPO that was oversubscribed 55 times over.

VCs recently poured $274m into over 49 deals in India in third quarter of 2008 (up from $252m into 36 deals in same period in 2007) – a sign that investment in India is still very much alive despite the financial market melt-down over the past few months.

The largest investment in the third quarter of 2008 was $18m raised by online tutoring services provider Tutorvista from investors Sequoia Capital India and Lightspeed Ventures.

The first three Proto events, in Chennai, saw IIT-incubated startups among the presenting companies – including wireless technology businesses, firms devoted to selling wikis, blogs and all the other paraphernalia of web 2.0.

Now Proto has moved on to New Delhi in 2008 before going on to other Indian cities to spread the entrepreneurial word.

“The past three editions of Proto.in have been in Chennai and the impact it has created here has been phenomenal,” says Proto founder Vijay Anand. “The level of support that entrepreneurs have, all the way from simple discussions and falling back on each other for help, to socialising, to the level of confidence that has been inspired in local entrepreneurs, has been something beyond which we expected to see.

He adds: “I am starting to see more and more Indian companies built and focused on solving Indian problems first and then moving from there.”

One of the most innovative startups is DesiCrew, a Chennai-incubated company which exhibited at Proto in 2007.

The name “DesiCrew” explains what Malhotra’s company is about. “Desi” is a colloquial word that refers to anyone from the Indian subcontinent; the “crew”, in this case, are rural business workers, working remotely on tasks such as translation, data entry, research, and plotting for GIS (geographic information systems).

The company is headed by the quiet but dedicated figure of Saloni Malhotra, a woman who, after hearing Jhunhjunwala articulate his vision for India, left a highly paid job at a software company in Pune to set up a firm which could bring employment to rural India.

DesiCrew has developed an IT system that allows people with basic English and basic IT training to perform such business tasks in rural areas.

The workers, mostly unemployed graduates, log on to a multimedia PC at an internet-enabled village kiosk. Many are educated young women who have no option but to stay in their villages to work. So far, there are six centres employing 70 rural people.

Those 70 include people like 25-year-old Thenmozhi, who comes from a community of weavers – and who now handles digitisation and data conversion projects in Appakudal, a town where according to the last census in 2001, only 41% of women were literate. “She would have remained a homemaker if this opportunity had not come her way,” says Ashwanth Gnanavelu, HR manager at DesiCrew.

“Jobs are moving from different countries to India,” explains Malhotra, “and within India from bigger cities to smaller cities - and given that you have computers, connectivity and skilled people, how far can you take the jobs? Can you take them to a small rural area where people are trained on whatever process you want them to work on?”

“We thought the opportunity was across India – around 15,000 internet centres have been set up in rural areas, in the name of bridging the digital divide.”

But if DesiCrew is to grow, then it needs that rural infrastructure to grow too. “Seamless connectivity and stable power supply are the need of the hour,” says Gnanavelu, who has chosen the rural teams and trained them. “We still have a long way to go in terms of scalability, proving sustainability and handling highend tasks.”

Jhunjhunwala is supportive. “Can we take production work that doesn’t require too much energy, that uses a lot of human skills and labours, to the rural areas?” he asks. “Why not? Incomes are very small, but then we use computers and communications, and we take care of transport and do remote management.

Eventually that will drive wages up,” he says. “Our aim is to make sure the per-capita rural GDP doubles. This simple thing will create confidence. It will make rural India a huge market.”

Other Indian companies, too, are pursuing a “desi” business model. Last year I met Anurag Dod, CEO of Guruji.com, a search engine that aims to be the Google of India – and drank beer with him by a pool at a Silcon Valley style team-building session with his staff, soon after he had secured $7m in funding from Sequoia, one of the biggest venture capital firms in India.

A year on, Dod is applying for second-round funding, and is bullish about the way India is becoming less of a development hub and more of a market of its own, with rising consumer spending leading to growth.

Yet if Guruji.com is going to compete with the likes of Google, it needs to target an Indian consumer – and that means focusing on regional content. These days it offers searches in no fewer than eight languages: English, Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi and Gujarati.

Targeting the regional internet is not Dod’s only goal; Guruji offers mobile searches, location-based content, and searches exploiting those two twin poles of Indian cultural consciousness, cricket and Bollywood. But the plan illustrates the conundrum for the Indian web 2.0: in order to see growth at the rates that venture capitalists may demand, businesses may need to reach at least part way across the yawning digital divide.

Dod, of course, can quote those all-important internet penetration figures without hesitation. Currently, he says, there are about 30 million internet users in India – and while that’s only a few per cent of the total population, he argues, it’s grown twenty times in eight years and is comparable in size to the number of internet users in South Korea; although in South Korea, broadband penetration is much higher.

That said, China already has 210 million internet users – and if that’s a measure of where India is going, then there are growth opportunities for sure.

Dod sees the opportunity among India’s middle class. “If you look at the possible internet penetration, if you consider the middle class, then the numbers are very small,” he says. “The growth opportunity of the internet is huge. And that’s where our opportunity lies.”

“Every product that has been successful in the global market has at first been successful in its home market,” says Anand, who organises the Proto event.

“It is an oft-quoted statement that India is in a fabulous position of growth at the moment; if we do figure out what works in India, an emerging market, we potentially have the key to tap into five-sixths of the world markets – and that’s bigger than the western market in all its entirety. It’s partly the long-tail concept all over.”

But for the runners in the race for Indian internet eyeballs, the danger is that the Indian internet market has not yet matured as quickly as it might. “E-commerce is picking up radically here,” says Proto organiser Anand, but adds: “I think it’s (19)99 here, in terms of the adoption of the web.”

Of course, in the US and Europe, the 2000-03 dotcom bust happened partly because valuations had got ahead of infrastructure and connectivity – which emphasises the importance of getting Indians online.

One way is by exploiting the Indian love of their mobile phones. There are more than 200 million users of mobile phones in India – and within two years the country is expected to have 20 million users of 3G (third-generation) mobile networks, which are capable of supporting mobile internet at reasonable speeds.

That’s why Guruji has moved into mobile web searching – and why some of the biggest receivers of funding have been companies who exploit the mobile web.

They include OnMobile, which has won a string of technology awards and raised about $124m via its IPO in January 2008; and Mobile2Win, which provided SMS services for the TV show Indian Idol last year.

Amit Ranjan, an entrepreneur who runs Indian technology startup blog WebYantra, says that given the penetration of mobile phones into the Indian market, products and services based on mobile devices are likely to be targeted at rural areas. “Cellphones have become ubiquitous in the rural areas due to large scale adoption; the same is not true for computers,” he says.

Needless to say, there are businesses who aim to change all that. Midas Communications, for example, is an IIT-incubated company that focuses on wireless broadband connectivity, and made the Red Herring Asia list of top 100 companies in 2006 – and has ambitious expansion plans. Given the lack of copper-wire infrastructure, wireless connectivity solutions are seen as a potential solution in the developing world.

Yet Anand points out increasing internet penetration is about more than just putting the technological infrastructure in place. “The issues though come in other forms, as we try to tackle 650 languages, and the diverse range of literacy and qualified professionals,” he says.

Yet technology can help to bridge those chasm toos. Another Chennai IITincubated company who has exhibited at Proto is Novatium - a firm rising in global popularity thanks to its sub-$100 “thin client” PC.

Bankrolled by Sequoia and by Rajesh Jain, the entrepreneur who famously made up to $120m from selling the IndiaWorld internet portal in 1999, Novatium is hardly small fry. But its plans - to increase the number of PC users by bringing affordable computing to middle-class Indians, as a way into the rest of the market - could help bottom-up entrepreneurialism across the whole country.

Jain, the brains behind by the company, is no flashy dotcom mogul. He regularly updates his personal blog about emerging technologies, Emergic.org, and he’s famous for his frugality - one journalist for Newsweek magazine wrote that he lives “more like a monk” than a millionaire.

One of Jain’s complaints is that, despite the presence of large venture capital firms, there has been a shortage of angel investors and business mentors to allow smaller business get off the ground in India - which is why he’s put his money where his mouth is, spurning the trappings of wealth in order to invest in businesses that can help create social change.

“You need to let a thousand flowers bloom,” he says. “That’s where a lot of time, a lot of capital has to go - people need to try out 200 different ideas and out of that will come innovation, out of that will come the things that will succeed."

“Money is to be used as an instrument of bringing about disruptive change.”

Jain is a born businessman who gets his kicks from the highs and lows of life as an

entrepreneur. “We’re trying to build out tomorrow’s world. We’re trying to create

things that don’t exist - that others are not thinking about doing,” he says.

With Novatium, Jain noticed that, in a population who for the most part cannot

afford internet access except at public kiosks or at the workplace or schools, a

cheap internet-enabled computing solution is an immediate need.

And making use of Jhunjhunwala’s experience in the telecoms industry - the company has been incubated at IIT Chennai - he was able to create a new “thin

client” PC at a price point that Indians can afford.

His approach - to use “dumb” computers with full connectivity such as USB ports

and broadband accessibility, but whose data and applications are stored on a

central server, and which use your existing TV connection, removing the need for

a dedicated broadband network or even a monitor - brings down the cost of an

internet-enabled home or office computer to around $10 a month.

Because the system uses existing cable TV networks, the product - the Nova

NetPC - cannot reach rural areas. But for 12-year-old Selvi, a schoolgirl in the Chennai suburb of KK Nagar, it is changing her life.

At school, Selvi is taught programming languages - a sign of the strong emphasis

on technology in Indian education - but doesn’t get much of a chance to use a

computer to put what she has learned into effect.

But with a NetPC, she’s able to do her homework online, as well as checking her

email and visiting the internet site she wants - in other words, most things that

children in developed nations take for granted. To the envy of her classmates, she

scored 100 out of 100 in a recent test.

“I can learn how to operate it easily,” she says. “In my school they teach me only

the languages like C and DBase. So it’s easy to operate it here, and you can do anything. “I go to games sites, and Cyberfocus India. Anything about science and

technology, I’ll go.”

“We’ve got to look at doing things right to build the foundation for tomorrow,”

says Jain. “People think about the physical infrastructure - the airports, the roads.

They forget there’s the equally important element, the digital infrastructure.”

Of course, in a country as vast as India, there are millions of children like Selvi who

could benefit from a product like the NetPC - not to mention in other developing

nations, too. As well as customers in Chennai and Delhi, Novatium also operates

in Mauritius and Thailand.

Potentially, Novatium stands to reach a huge audience - a fact not lost on the

US technology giants who have visited in the Novatium pilot scheme in Chennai.

But Novatium has now announced plans to raise more than $10m in order to

scale up its operations.

But with rural infrastructure yet to be developed, and rates of poverty as high as

26%, the company must focus on urban areas for now. “You have to create models which are self-sustaining,” says Jain, in defence of that policy. “The way to the bottom is through the middle. Make it work in middle-income India, where people are willing to pay, but they can’t pay what the developed market charges.”

Anand points out that middle-income Indians represent 40% of the country -and in a land of a billion people, that is 400 million people. “If they sell their $100 units to each one of them, or conservatively aim at 10% of that market, that’s $40bn. I think that’s an amazing number to target, isn’t it?”

Anand also points to a much smaller company as an example of an Indian firm

that can help change lives through technology. The company, Eko, is a mobile based system for financial transactions – which aims to help extend banking

facilities to rural areas. The company, which is presenting at the latest edition of

Proto.in, is part of a wave of efforts to bring finance to the rural poor.

Another Chennai-based company, MokshaYugAccess, this year raised $2.1m in

private equity, as it attempts to provide affordable microfinance to the rural

poor in 356 villages in the Bagalkot district, 500 miles north-west of Chennai.

Without ways of bringing finance to village communities, says Jhunjhunwala,

there is little incentive for innovation on a rural scale - cementing the divide

between the haves and the have-nots. He says that microfinance interest rates

need to be affordable, so that the cost of servicing a loan is not crippling to a

smallholder or farmer who wants to invest.

But there can be financial benefits to even the simplest technologies. Webcams

can be used to diagnose problems with crops; and farmers can access information on weather and local market price movements, so that they can more effectively plan their crops and negotiate a fairer price for their produce.

In pilots, eye specialists from Aravind Eye Hospital, at Theni in Tamil Nadu, even

use healthcare videoconferencing as a diagnostic tool – so that villagers with

cataracts, for example, can have their problems diagnosed remotely rather than

travelling to hospital in town.

All reasons why Jhunjhunwala is adamant that using the IT revolution to create prosperity in rural India is an essential goal.

“Going back to when I was younger - there was no confidence that we can do it

in India. That confidence has come.”

“You need to let a thousand flowers bloom,” he says. “That’s where a lot of time, a lot of capital has to go - people need to try out 200 different ideas and out of that will come innovation, out of that will come the things that will succeed.

”